6.7 KiB

layout, title, date, comments, tags

| layout | title | date | comments | tags |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| post | Resurrecting an old plotter | 2019-02-23 | true | plotter, art, python, hardware, recurse |

I finally decided to give in to FOMO on #plottertwitter and bought an old plotter off ebay. Me being in batch at Recurse Center helped a lot, from the decision to get one to nerdsnipe Alex into collaborating with me. All of the work below is done with him.

What is a plotter anyway?

Plotters are graphics devices that can transfer vector images onto a physical medium. The core mechanism of a plotter is an arm that can move a pen in 2 axes (w.r.t the medium) and ability to pick up or place down the pen to draw. Versions of plotters exist where paper is replaced with other flat materials like vinyl or pen with a knife to make it a cutting plotter.

I like to think plotters as the naive solution to the problem that computers should be able to draw. Smaller, expensive memory chips (or magnetic cores) in earlier computers made working with raster images hard, and plotters didn't need much operating memory.

HP7440A

HP7440A "ColorPro" was an affordable plotter manufactured by HP, it can hold and switch between 8 pens simultaneously and draw on surfaces as large as A4. HP Museum has a longer post about this plotter

Ours came pretty unscathed, with original manuals!

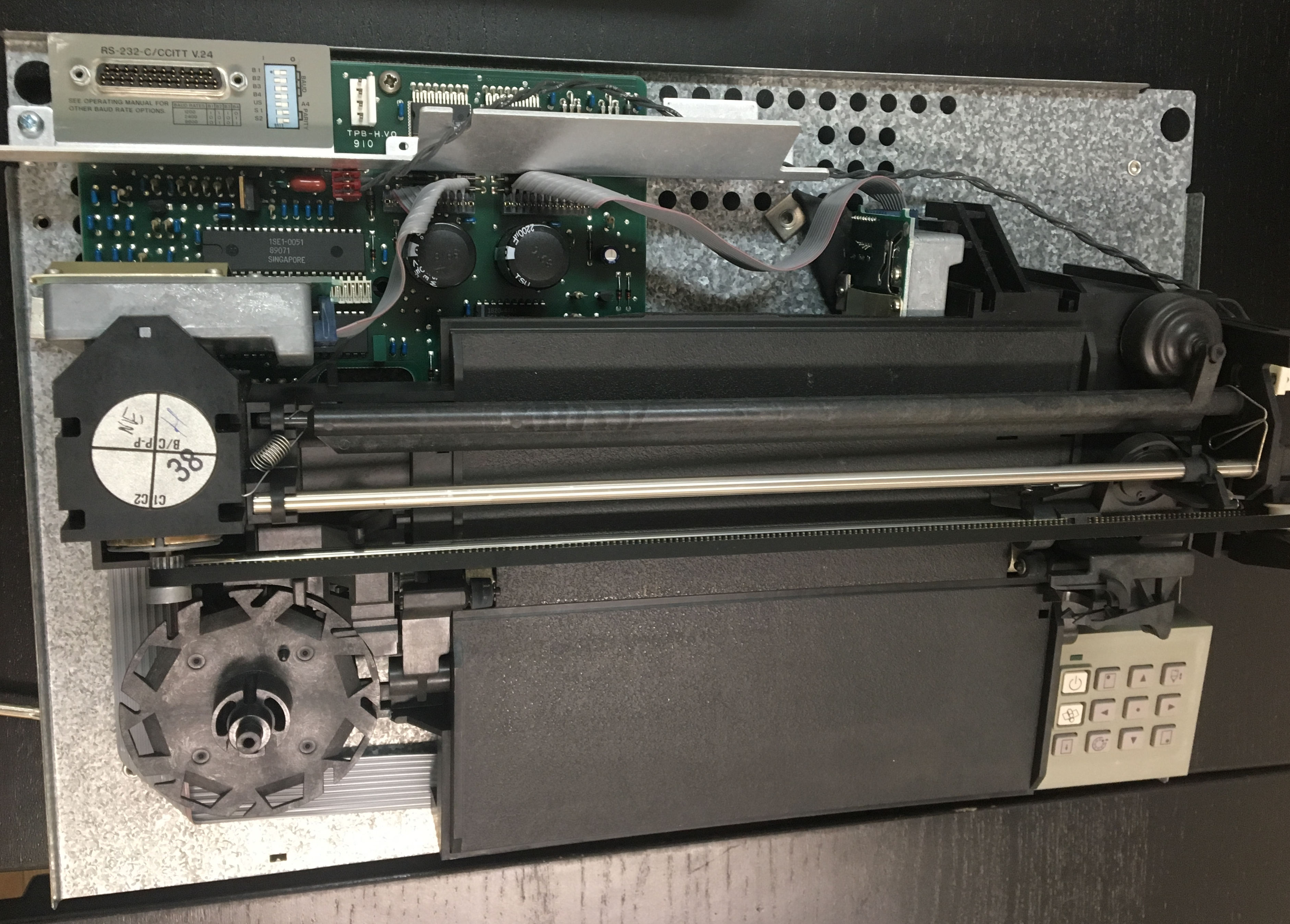

First thing we did was to open and clean it. I was quite surprised by how easy it is to open, take that 2018 tech!

The internal mechanism is pretty simple, There are two servos. One for moving the paper back and forward, and the other for moving the pen left and right. There is also a solenoid based lever to switch pen down and up.

Talk To Me

However, our plotter didn't come with any cables to either power it or to send commands.

Power supply was the biggest mystery. After digging through the manuals, and the

hand drawn schematics from HP

Museum, we managed to identify it to

be a 10-0-10 AC to AC. Luckily someone was selling one in ebay, but we could've

built one ourselves if not.

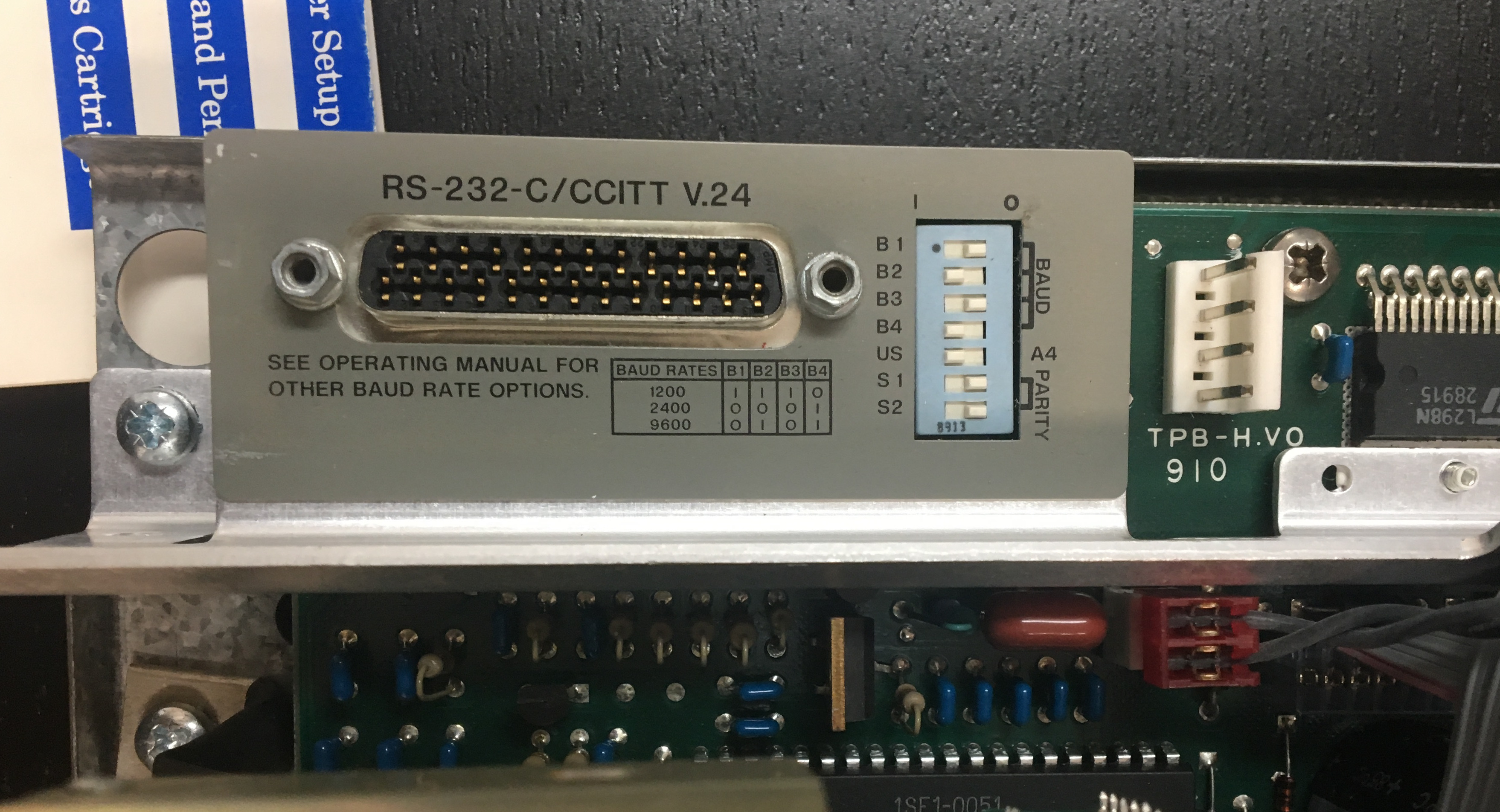

Communication turned out be just standard serial, however our plotter has a

DB-22 adaptor, so we had to use a DB-22 to DB-9 adpator and then DB-9 to

usb adaptor.

The final step was writing in the only language the plotter can understand,

HP-GL or HP Graphics Langauge. Lucky

for us, HP was on top of the plotter game when plotters were popular, so HP-GL

has become a de facto standard for talking to plotters.

.. and finally our plotter moves!

Goooooooo faster.

HP7440A has a limited amount of buffer space (about 60 bytes), so if we send a

longer command list to the interface, it will just drop bits after 60 and crash.

Our first naive solution was to add 1s sleep between sending subsequent

commands, however this made drawings really slow and added artifacts from

ink bleeding while the plotter is waiting for the next command.

Another recurser Francis pointed us to a clever hack in the wait function

in hpgl.js. This function uses the HPGL command OA; to block execution

until the plotter is finished with the current instruction. When the plotter

executes OA; it sends the current pen position, but it first needs to

wait until the pen has stopped moving. Thus we can batch a bunch of commands

and append it with OA;. As soon as we see the position over the serial,

we know that the previous batch is consumed and we can send the next batch of commands.

The code for it looks like this:

import serial

# combine command together with maxlen buflen and expose as an iterator

def stitch(body, buflen=40):

start = ["IN;PU;", "SP1;"]

end = ["SP0;"]

final = start + body + end

## read in 20 bytes at a time or boundary

count = 0

buf = []

for ins in final:

if count + len(ins) >= buflen:

yield "".join(buf)

buf = []

count = len(ins)

else:

count += len(ins)

buf.append(ins)

# send rest of the code

yield "".join(buf)

# cmds is a list with semicolon attached to the command

def exec_hpgl(cmds):

port = "/dev/cuaU0"

speed = 9600

body = stitch(cmds)

with serial.Serial(port, speed, timeout=None) as plt:

for ins in body:

# size (Esc-B) returns bufferlen

plt.write(ins)

# For block sent, end with OA, which reports back current

# position on the pen

plt.write("OA;")

c = ""

data = ""

while c != '\r':

c = plt.read()

data += c

print("read: {}".format(map(ord, c)))

print("OA return: {}".format(data))

# We got data, mean OA got executed, so the instruction buffer

# is all consumed, ready to sent more.

This made the plotter super fast!!!

Everything's a line anyway!

After initial success we quickly realized our plotter does not respond to any

commands that involved HP-GL instructions to draw basic geometry, like CI for

circle.

A re-reading of the manual made us realize HP sold these functionality as an hardware adaptor board that plugs in the bottom, which we don't have.

But everything in computer graphics is a line anyway, right? With some root of unity math, we came up with a circle drawing routine.

This is only the beginning

Hardware wise, only thing remaining to fix is our pens, which expired in 1996! We are yet to come up with a strategy to refill/replace them.

I am also going to leave this plotter at RC, so that other recursers can continue hacking on it, and get another one for me and actually do some generative art. :-)

Notes

- Big thanks to Amy and Francis and Alex S for their help at various points.

- All of our python code is here: https://github.com/dbalan/plotter-scripts

- Thanks Tom for proof reading this post!